For a generation that remembers where they were when the news broke about John F. Kennedy Jr.’s plane, Ryan Murphy’s “Love Story: John F Kennedy Jr & Carolyn Bessette” lands with a complicated thud. It is lush, stylish, and starry, yet it walks straight into the most sensitive parts of the Camelot myth and begins rearranging the furniture.

TLDR

Ryan Murphy’s new dramatization of John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette leans into glossy romance and fairy-tale nostalgia, while critics argue it blurs documented tensions in their marriage and unfairly reshapes responsibility for the fatal crash.

Glamour vs Grief Onscreen

Murphy has built an empire on turning real-life headlines into prestige melodrama, and “Love Story: John F Kennedy Jr & Carolyn Bessette” fits neatly into that brand. The series bathes John and Carolyn in warm light, immaculate tailoring, and cinematic yearning. Their New York nights look like perfume ads. Their arguments feel carefully choreographed, less like a crumbling marriage and more like a lovers’ quarrel that will inevitably end in a kiss.

For some viewers, that level of glamour offers a kind of emotional escape. It lets them revisit the 1990s through the most photographed couple of the decade, complete with slip dresses, blowouts, and the fantasy that Camelot might have survived if fate had been kinder.

But the fairytale is precisely what is under fire. In her blistering DailyMailUS column, Maureen Callahan calls the project “beautiful to look at but empty inside,” accusing it of sanding down the roughest edges of a real relationship and a real catastrophe. She argues that this version of John and Carolyn is not only softened, it is also strategically rewritten.

That tension between high gloss and hard history is the beating heart of the backlash. When the subject is two people who died young and violently, the choice to lean into fantasy carries reputational weight for everyone involved, from the director to the estate to the actors stepping into those ghosts.

The Real Couple Behind the Myth

Part of why the series stirs such emotion is that the real story of John and Carolyn has never been simple. According to People, friends described the couple’s romance as both magnetic and difficult, a relationship that swung between intense affection and equally intense conflict. Their wedding on a secluded Georgia island in the 1990s looked like a royal tableau, but those who knew them recalled mounting pressures soon after.

He was America’s prince, raised in an atmosphere where attention was oxygen and risk could feel like destiny. She was a Calvin Klein publicist, suddenly hurled into a level of scrutiny almost no one is prepared for. Paparazzi camped on their doorstep. Every outfit, every cigarette, every moment of visible strain became tabloid currency.

Accounts over the years have described arguments in public, separations, reconciliations, and a marriage that was far from the effortless chic projected in photographs. People reported that those close to the couple saw Carolyn struggle with the weight of fame and the expectations placed on a woman married into the most mythologized American family of the 20th century.

Murphy’s series nods to some of this difficulty, but Callahan argues that the center of gravity is skewed. On screen, Carolyn often appears as the dazzling, cool girl who can take or leave John. Off-screen, biographers and friends have painted a more complicated portrait of a woman who worked hard on her image, pursued John, and then found herself overwhelmed by the cost of life in his orbit.

Rewriting a Fatal Night

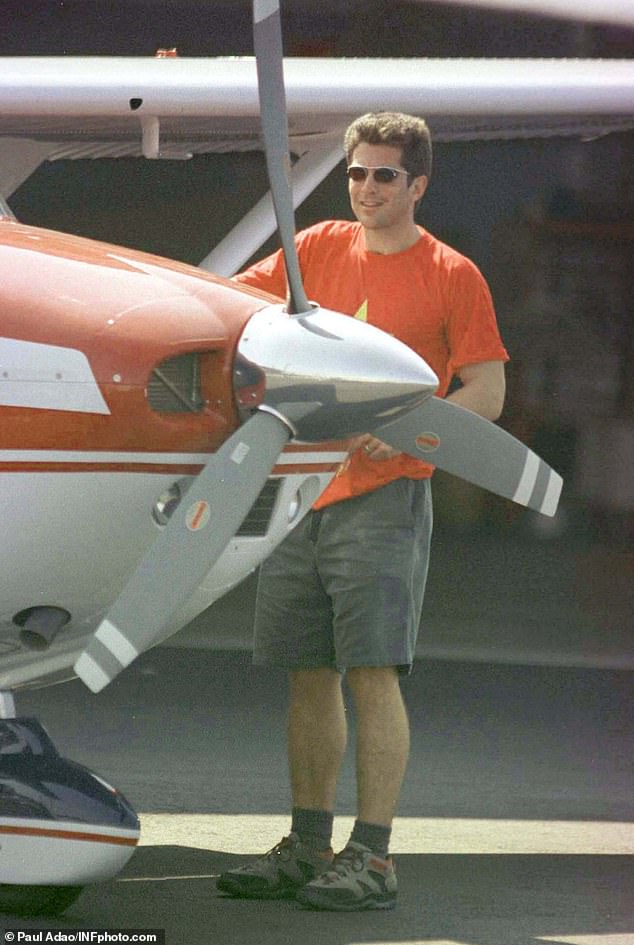

The sharpest criticism, though, is reserved for how “Love Story: John F Kennedy Jr & Carolyn Bessette” handles the night of the crash. In the premiere, Carolyn is shown delaying the trip for something as trivial as a manicure redo, which forces John, a relatively inexperienced pilot, to take off after dark. It is a familiar rumor, but critics argue it is also a sexist one that has never been substantiated.

Callahan notes that federal investigators placed responsibility for the tragedy squarely on John. In her column, she points back to findings from the National Transportation Safety Board that John lacked crucial instrument training, failed to file a proper flight plan, and flew into deteriorating visibility. According to her reporting, the official record treated the crash as a textbook case of pilot error, not a morality play about a difficult wife.

By dramatizing the manicure story as a pivotal cause, the series does more than add narrative tension. It assigns narrative blame. In a culture that has long been quick to fault women for the downfall of powerful men, that choice is not a small one. Viewers who remember the wall-to-wall coverage in the 1990s will recall how quickly gossip hardened into “truth” about Carolyn’s supposed vanity and coldness.

The show also alters quieter details in ways that disturb some who have studied the case. Callahan points out that the series depicts Carolyn and her sister seated behind John, facing forward, when in reality they were strapped in facing away from him, their backs to the cockpit. It is a seemingly small staging difference, yet to those who care about accuracy, it signals that aesthetic choices are being prioritized over the grim logistics of what actually happened.

Jackie O and the Weight of Legacy

Even beyond John and Carolyn, “Love Story: John F Kennedy Jr & Carolyn Bessette” steps into hallowed territory when it reaches for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. The series reportedly shows Jackie alone, drinking, pining over a husband who humiliated her publicly and privately. For critics like Callahan, this is another place where the show confuses drama with disrespect.

In reality, Jackie spent her later years in New York as a respected book editor, a woman who rebuilt a life of work and friendship after unimaginable losses. Public accounts of her marriage to President Kennedy acknowledge the infidelities and the power imbalance, yet they also show a woman who learned to negotiate, survive, and eventually define herself apart from the presidency.

When a modern series turns that woman into a kind of sentimental ghost, swooning over a man who left her alone in some of her darkest moments, the symbolism is potent. It can subtly reframe her, and by extension other Kennedy women, as supporting characters in the tragedy of brilliant, broken men rather than as protagonists in their own survival stories.

Callahan has said that hearing this fictional Jackie use casual phrases she never would have used in life, such as “anyways,” felt like a small, almost petty betrayal that signaled a larger carelessness. In her view, even the dialogue choices matter when the subject is someone whose every syllable was once parsed like scripture.

Why This Story Still Hurts

The stronger the reaction to Murphy’s latest project, the clearer it becomes that John and Carolyn still belong not just to history, but to memory. For Gen X and Baby Boomer women in particular, Carolyn embodied a very specific fantasy of 1990s womanhood: minimal, chic, elusive, walking the streets of Tribeca with her hair in her face and a city at her feet.

Her sudden death, at 33, snapped that fantasy in half. The grainy images of search boats on dark water, the breathless cable updates, the endless speculation about what went wrong all fused into a single national ache. To watch that night restaged now, decades later, with fresh faces and careful lighting, is to reopen a wound that never fully closed.

For some, the chance to revisit John and Carolyn through a big-budget series feels like a way to say goodbye again, this time with context and nuance. For others, it feels like an intrusion, or worse, a distortion that threatens to calcify into the new default version of events.

That is the power and the danger of prestige television about real people. A show like “Love Story: John F Kennedy Jr & Carolyn Bessette” will likely reach far more viewers than any investigative book or official report ever did. Its choices about who was brave, who was cruel, who was reckless, and who was wronged will linger in the cultural imagination long after the credits roll.

Murphy has always been most interested in the emotional truth of his characters, not in serving as a historian. Yet when the people in question are Kennedy heirs and the women who loved them, emotional truth and factual truth are forever entangled. Every scene is a negotiation between drama and documentation, between catharsis for the audience and fairness to the dead.

In the end, “Love Story: John F Kennedy Jr & Carolyn Bessette” asks viewers to lose themselves in a beautiful, doomed romance. The growing chorus of critics asks something else entirely. They want us to remember that behind the legend was a frightened couple in a small plane on a dark night, and that how we tell their story now will shape how they are remembered for years to come.

Join the Discussion

How do you think filmmakers should balance emotional storytelling with factual responsibility when they dramatize real people like John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette?